Microtranist Is Taxpayer Funded Uber, Advocates Warn — And It’s a Threat to Real Transit

American cities are falling for the "false promise" of microtransit, a top transportation union argues — and we're all going to be the ones who pay for it.

Advocates are sounding the alarm that America's much-hyped "microtransit" services are essentially just app-taxis by another name — and they worry the harm they cause to drivers, passengers, and our communities could be even worse than Uber and Lyft over time.

According to a new report from the Amalgamated Transit Union, app-based, on-demand "microtransit" services are exploding across America, with at least 100regions either complementing or outright replacing their traditional fixed-route vehicles with sedans, vans, or cutaway bus shuttles. And much like the early days of Uber, these services offer a tantalizing promise: taxi-like, door-to-door service, give or a take a few detours to pick up other passengers going in the same direction, in dense city neighborhoods and far-flung rural areas alike — and all for a price on par with a traditional bus ticket.

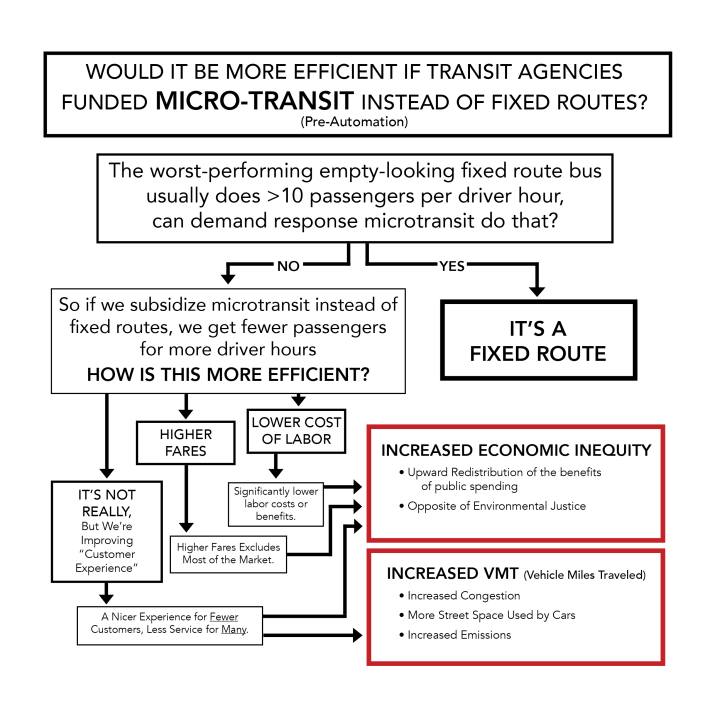

If that sounds too good to be true, the union argues, it is. Microtransit costs already cash-strapped agencies two to three times more per passenger than even their worst-performing bus routes, the report said.

And some regions, like Los Angeles, ponyup eight times more than on their traditional lines. That's in part because, despite microtransit companies' big ride-sharing promises, few passengers are actually going anywhere near one another at the exact same time — leaving some agencies, like Maryland's Montgomery County, delivering single-person rides 90 percent of the time, essentially eliminating the emissions, congestion, and other VMT-reduction benefits of public transportation.

That kind of dirt-cheap mostly-private chauffeur service, of course, is bound to be wildly popular — and when demand rises, transit agencies are quickly forced to make difficult choices to continue offering it. Some opt to raise fare prices, leaving poor riders out in the cold; some are forced to deny requests for rides they can't handle, leaving passengers stranded or unable to make it to work. One agency in Park City, Utah, for instance, saw microtransit wait times swell to an average of 27 minutes, with a third of passengers waiting between 30 and 60 minutes total; 20 percent of trip requests in two particularly transit-poor neighborhoods went unfulfilled completely.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the report authors found that in several cities, microtransit was more likely to serve white, able-bodied and affluent residents than the BIPOC, disabled, and low-income passengers who rely on low-cost mass modes the most. One driver mentioned a particularly frequent passenger who regularly took microtransit to dinner at the local country club; others mentioned that many of their low-income, car-free customers don't have smartphones at all, never mind apps to summon a ride that might never come.

Despite this, some agencies still choose to do whatever it takes to keep microtransit going — including cannibalizing funds from fixed route transit, accelerating a death spiral that's already been spinning faster since the pandemic. The researchers say agencies like Sarasota, San Antonio and Green Bay have already "eliminated directly operated bus service in favor of microtransit operated by independent contractors" — and they suspect more will follow suit.

"[Agencies] can get a grant for two or three years to throw some [microtransit] service on the street and say that they did something. But what do you do when that grant funding runs out?" said Andrew Gena, director of strategic research for the Amalgamated Transit Union and the lead author of the paper. "If the service becomes popular, it becomes too expensive; that's just the nature of how it works. And so at the end of three years, they're going to be forced [to answer] a question: are we going to take more money away from fixed route service to fund this boondoggle?”

For all its hidden downsides for passengers, though, Gena says that some of the biggest and most overlooked victims of the microtransit grift are its drivers. Click to view larger.Graphic: Human Transit

Click to view larger.Graphic: Human Transit

The public may not realize it, but many microtransit operations are contracted out to private companies like Via and RideCo, which promise agencies a "turnkey" service complete with vehicles and an army of largely part-time, non-unionized gig workers to drive them. Also much like Uber, these drivers don't receive basic benefits or guaranteed working hours; some are even required to lease their vehicles from the microtransit outfit and fuel them up themselves.

"Everybody understands how Uber and Lyft constantly screw over their drivers, right?," adds Gena. "We see a lot of similarities with [microtransit] — and in some ways, it’s even worse, because we're funding all of this with our tax dollars. At least with Uber and Lyft, people are paying out of their pocket. But if someone's paying $1 or $2 for a micro transit trip that might be costing the agency $40 or $50, we're all subsidizing an inefficient service that incentivizes the destruction of good jobs.”

Union President John Costa puts it even more bluntly.

“It's the same thing as Uber," he says. "That's what it is. Just like we have Uber Eats, now we have Uber vans ... It's all bullshit, and at the end of the day, it's going to hurt the passengers, and it's going to [result in] fewer people getting on public transit in general."

Instead of just jeering at ride-hail companies for attempting to re-invent the public bus at a higher cost, Costa and Gena argue that advocates should take note of how agencies are Uberizing their own service by contracting with Uber-like microtransit companies — and urge them to re-invest in improving their core service instead.

Over time, the researchers argue, those investments will increase ridership, and better position agencies to provide in-housemicro-transit service in the limited situations that are actually worth the steep subsidy to decrease fares while still paying union workers what they deserve. That includes providing accessible paratransit vans to people with disabilities, piloting service in new neighborhoods that might someday get a dedicated route, and providing those elusive last-mile connections.

In most other cases, though, Gena argues that microtransit is a dangerous idea that we should regard with skepticism.

"People need to ask: 'is this really the best way to use our use our limited resources for transit?' he adds. "Or do we need to be get serious about improving our fixed-route services?”

(source: ATU.org)